Independent study suggests exposing residents to the benefits of primary care, working to develop PCP training opportunities and being more receptive to relying on advanced clinicians like NPs and PAs

by Intelliworx

Primary care may have an outsized impact on the overall health of a population. As the saying goes, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

But there’s more than just an old quip as evidence – there’s data:

“Studies have repeatedly shown that having this regular, or usual, source of health care improves patient outcomes and reduces unnecessary utilization of emergency rooms and hospitals.”

That’s according to a report and “primary care scorecard” by The Physician’s Foundation and the Milbank Memorial Fund. The report is built on top of a previous study by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM).

The report concludes there’s an acute shortage of primary care providers (PCPs) in the U.S. and the immediate cause is straightforward: too few medical students are pursuing careers in primary care – and of those that do become PCPs, tend not to stay in the field.

The primary care shortage is growing

This staffing problem is getting worse too, the report found.

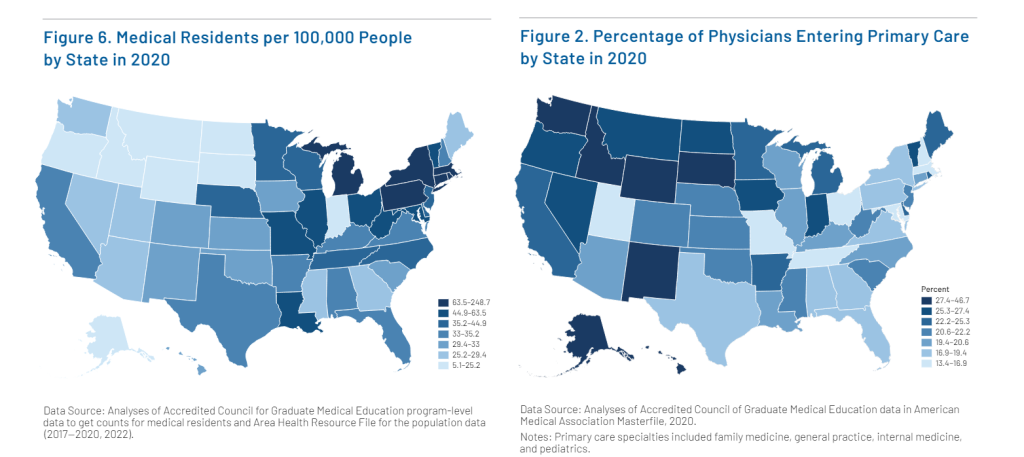

Currently, about one in three U.S.-based physicians are PCPs, but the pipeline of talent is shrinking. For example, the report says among all physicians who completed residency between 2012 and 2020 – just one in five “were practicing primary care two years later.”

While the shortage of staff affects all geographies, rural communities in particular are being hit the hardest, Dr. Yalda Jabbarpour, who led the study, explained to The Daily Yonder.

While there are many other contributing factors that have been well documented in study after study, this particular report is noteworthy for the solutions sprinkled throughout.

Below are some of the solutions the report floated that stood out for us.

1. Do a better job exposing more medical students to primary care

The Northeastern U.S. has the greatest density of doctors-to-population (upwards of 80 doctors for every 100,000 people) – but the fewest who enter PCP providers. This means many of those doctors in the Northeast specialize in something other than primary care.

At the same time, rural areas have far fewer doctors. While most of the doctors in rural areas enter and stay in PCP, on a comparative percentage basis, the overall volume is far too low which adds to the shortage.

The report puts it this way:

“The mismatch between training opportunities and PCP supply signals that graduate medical education (GME) funding is not set up to support the growth of primary care but instead encourages subspecialty fields. In fact, most GME funding is allocated to the sponsoring institution (usually a hospital) even though primary care occurs in the community rather than the inpatient setting.”

In other words, the education system should be placing a greater emphasis on exposing medical students to primary care – rather than specialties. There’s an opportunity to develop programs to expose residents to rural or community-based health initiatives.

To that end, David C. Dugdale, MD, one of several subject matter experts interviewed in the report, addressed some of the benefits of being exposed to rural healthcare:

“The unbound nature of primary care, the open-ended commitment brings certain positives with it that I think many other clinicians simply don’t experience. I have valued the intimate knowledge of people’s lives and circumstances as they relate to my trying to do the best job I can vis-a-vis their health care. I think, for the most part, that holistic view isn’t hardwired into the field in other specialties.”

In a separate survey, we asked providers what they thought were the top benefits of working in rural areas and the top answers were “lower cost of living” (47%), more time with patients (46%) and “better work-life balance” (45%).

(Click for larger image)

2. Implement community-based training programs

Doctors tend to stay and work wherever they are trained. For example, teaching hospitals are in major urban areas – and when doctors complete their residencies they stay.

One solution is “community-based training initiatives” which “have been shown to produce graduates who are more likely to care for underserved patients and work in rural areas.”

The report highlights one such program in Michigan by Authority Health:

“Seventy-eight medical residents across four specialties (internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, and psychiatry) have increased access to primary care, providing 80,000 patient visits a year that would not exist without the THC program.

How does it work?

“Residents (doctors) deliver primary care to patients through a multidisciplinary group-practice model integrating doctors with nurses, social workers, and other health professionals in community-based settings.”

Is it effective?

“Since the Authority Health THC’s inception in 2013, 49% of graduates have stayed in Michigan and 62% are practicing in a medically underserved area.”

3. Broaden the of scope practice and build a pipeline of NPs and PAs

Nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PA) are promising options for addressing the shortage. Currently, NP and PA participation in PCP tends to mirror staffing trends with physicians:

“Along with primary care physicians, NPs and PAs are core members of the primary care workforce. In general, the states with a high percentage of primary care physicians also had high percentages of NPs and PAs – with some exceptions.”

The challenge is some states have more restrictive policies about what NPs and PAs can and cannot do without physician oversight. Yet at the height of COVID, many states expanded the scope of practice for NPs and PAs out of sheer necessity – and it was successful:

“For example, one study found that states that allow for NP autonomy see an increase in the number of NPs and in health care utilization among rural and vulnerable populations. Indeed, the states in this analysis with a high percentage of NPs working in primary care, such as Oregon, Idaho, and Nebraska, also have less restrictive scope-of-practice laws.”

There also seems to be evidence that advanced clinicians like NPs and PAs tend to stay in primary care once they enter it. For example, Nicole Seagriff, DNP, APRN, FNP-BC who was interviewed as part of the report noted:

“During the pandemic, colleagues and I surveyed our alumni and found that 92% of respondents were still working as a nurse practitioner in clinical practice, and that 74% were still practicing as primary care providers — the majority of that group were still at a federally qualified health center.”

However, the report is careful to add none of this is conclusive. There are some states – such as California and Oklahoma – that have maintained restrictive laws for NPs, but still have a high percentage of these advanced clinicians working in PCP.

While the hypothesis is sound, and there is supporting evidence, the researchers say it needs to be studied more.

“The lack of a uniform national data set that lists advanced practice clinicians’ current specialties limits a complete understanding of workforce data for NPs and PAs,” they wrote.

Modernizing healthcare processes and policies

The report also covers some more fundamental changes in healthcare that could help in the long term. For example, the report advocates changing how we pay for healthcare. This includes shifting incentives to “whole person care” and better health outcomes – as opposed to paying physicians for delivering services.

While something like that will take years to transform, there’s also some practical advice first-line leaders can do immediately and at no cost: thank your team.

As Kristina Diaz, MD, MBA, CPE, FAAFP, one of the experts interviewed in the report put it:

“I feel that one of the ways to draw more people to primary care involves the need to express gratitude for our primary care physicians – with words, action, and reimbursement.”

The full report is freely available online and is worth the while to peruse: The Health of US Primary Care: A Baseline Scorecard Tracking Support for High-Quality Primary Care.

* * *

One of our observations – not from the report – is that healthcare systems can make tangible improvements by getting their provider recruiting processes organized. This means performing a “practice analysis” to understand and forecast your talent needs – to improve recruiting and onboarding processes.

That’s why we made a Workforce Management solution specifically designed to support rural hospitals and healthcare. Check out this short video or contact us for a no-obligation demo.

If you enjoyed this post, you might also like:

Can hospitals really lose a provider to a disorganized recruiting process?